Three decades ago, the internet brought the promise of democratising everything. It was to remove the gatekeepers and allow us all to create and share our work.

The utopian vision of internet observers and commentators like Clay Sharky was that we’d all be able to disrupt the archaic institutions. Musicians like Bowie and Radiohead could bypass the record labels. And so could anybody else with a copy of Garageband and an internet connection.

The internet gave everybody access to the tools that would turn us all into independent creators across all media – art, music, writing, film.

The internet was supposed to give us sovereignty over our lives.

For a subset of rebellious entrepreneurs, this version of the internet made perfect sense and they capitalized on the opportunity. But they’re the kind of people who would have pursued their vision anyway, no matter what. They didn’t need the internet – it just made it easier. For others, there is a gap to bridge first.

The rebels had what sociologists call Agency. the capacity to take control of a situation. Agency is the power to marshal resources and create new possibilities.

Like most things, agency isn’t distributed evenly.

For generations, most of us were indoctrinated into the reliable, sage advice to get a good, reliable job. And by outsourcing our own job creation, we were dependent on others our whole lives. We were all taught to follow orders.

But reliable equates to reliant.

We became reliant on others – our parents, teachers, employers, and law-makers made our decisions for us. We surrendered to authority.

For most, it was an easy trade-off.

For a few, surrendering their agency to the highest bidder was unacceptable.

They each had a different version of the world that didn’t exist at the time. A world with motorised transport, human-powered flight, iPhones, the internet, the 4-minute mile, and the Fosbury Flop.

For them, following the consensus protocol for a successful life wasn’t an option. That version of the world didn’t contain their vision.

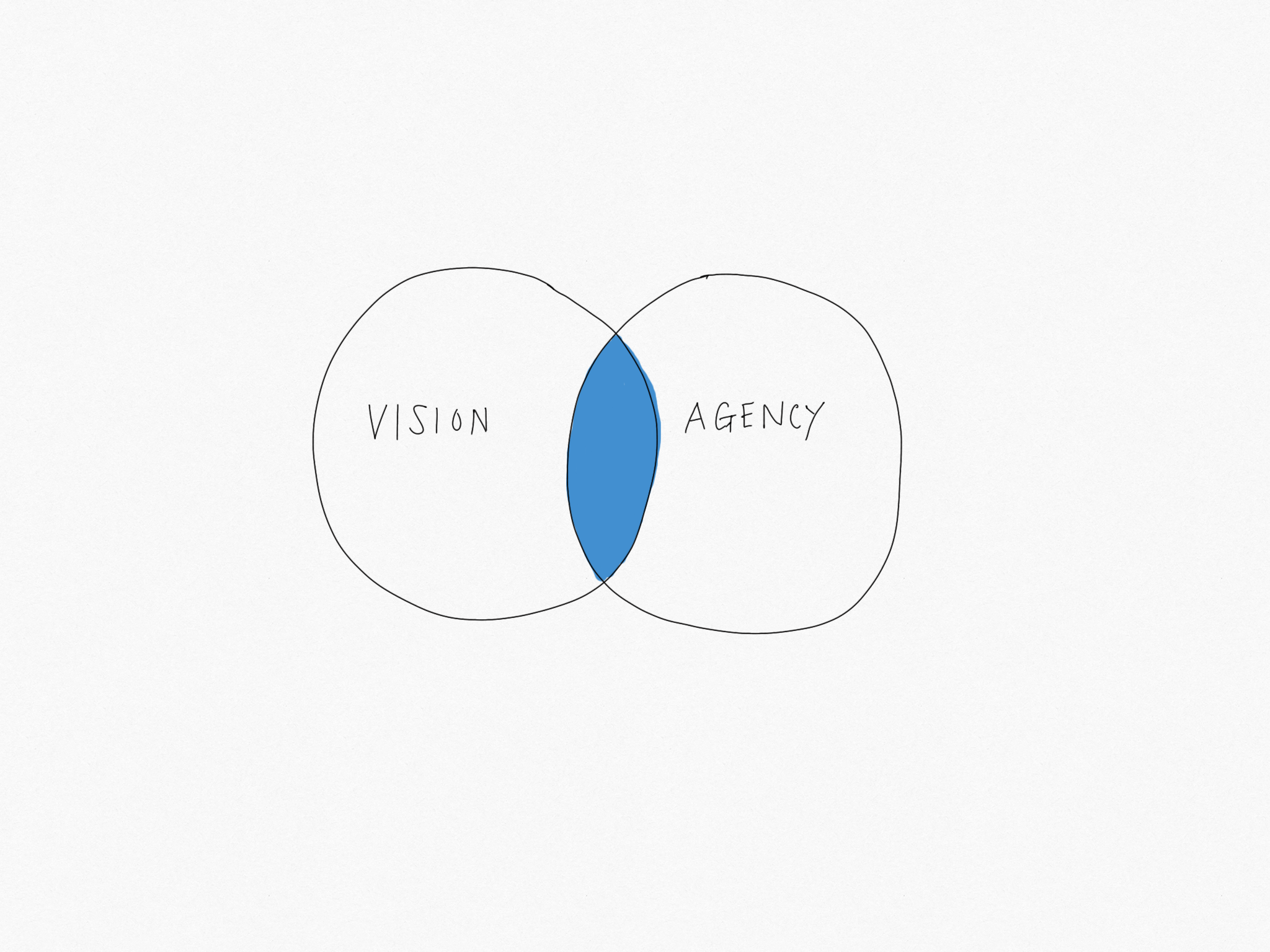

Fortunately, they were also outliers on the agency curve. They all possessed the rare Venn intersection of vision and high agency.

They had the vision to imagine and dream big impossible ideas.

And the agency to turn the impossible into reality, usually in the face of resistance and ridicule. Sometimes even when the odds are stacked against you – Elon Musk bet everything on Tesla, even when he thought it probably wouldn’t work, because — if it did — the expected value was worth it.

In the post-industrial age, as society transitions towards independent, sovereign individuals, agency is the hidden key to realising individual freedom and self-determination.

…which means for those who grew up reliant on others, there’s a gap.

There’s a particular Steve Jobs quote that I keep coming back to

Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact. And that is everything around you that you call life, was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use. Once you learn that you’ll never be the same again.

Steve is talking about agency. He’s not talking about changing the world, but finding out that you can.

Linguistically, its a subtle difference. In reality, a completely different message.

Vision and ability aren’t the differentiators. Agency is.

The inflection point is the moment you realise you’re free to do what you want.

“Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again”.

High Agency

Eric Weinstein was the first I heard to describe the concept of high agency. In an interview with Tim Ferriss…

When you’re told that something is impossible, is that the end of the conversation, or does that start a second dialogue in your mind?

How am I going to get past this bouncer who told me that I can’t come into this nightclub?

How am I going to start a business when my credit is terrible and I have no experience?”

Paul Graham uses a different term to describe the same phenomenon…

I finally got being a good startup founder down to two words: relentlessly resourceful.

Relentless resourcefulness describes high agency. It’s the same thing.

PG goes on to describe the opposite as hapless…

Most dictionaries say hapless means unlucky. But the dictionaries are not doing a very good job. A team that outplays its opponents but loses because of a bad decision by the referee could be called unlucky, but not hapless. Hapless implies passivity. To be hapless is to be battered by circumstances—to let the world have its way with you, instead of having your way with the world.

Once you understand High Agency, you begin to notice it everywhere that you find success. Anecdotally, the correlation between high agency and success appears so significant, there’s a robust case that it’s causal. At the very least, it’s a pre-requisite.

When the founders of Airbnb had maxed out their credit cards, they created political breakfast cereal called ObamaOs and sold it for $40 a box. They raised $30,000 and ate unsold stock to keep them (and Airbnb) alive.

Outrageous, right?

For most people, yes, it’s batshit. But with high agency, you get to have wild orthogonal ideas like this and the audacity to ask what if? What if it actually works?

Austen Allred is the Founder & CEO of Lambda School, where they’re reinventing education and professional credentials. A Twitter thread he wrote epitomises high agency:

…Many of you know I lived in my car when I first moved to Silicon Valley.

Few know that car broke down one day.

I would shower at the YMCA on Ross Road in Palo Alto and work out of the Hacker Dojo. On my way between the two it just stopped on the freeway. One day it just seized up, and I found myself in a dead car (that I lived in) on the side of the freeway.

The tow truck driver (who I keep in touch with to this day) offered to let me stay at his place, but I didn’t even have enough money to pay for the tow, let alone the repair – the combination of the two were going to run me $600 I didn’t have.

At the same time there was a billboard for a soccer game at Stanford Stadium. In the past I’d scalped tickets to make an extra buck, so I figured I’d give it a shot.

But even a great day of scalping wouldn’t make you $600, so I started looking around at the tickets online.

I started cold emailing and cold calling everyone that had tickets online, even though I couldn’t afford to buy any.

One guy had an extra 200 unsold tickets that were going to be worth $0. I convinced him to send them to me and I’d sell them and give him half.

So what do you do with 200 tickets and 24 hours to sell them? You just try to move them as fast as you can.

The difficult thing about Stanford Stadium is there’s no single entrance – no corner you can work.

Experienced scalpers all started showing up with bikes. Bikes! Genius.

The leader was named “Vegas.” We worked a deal. I sold tickets to him at a discount, and he and his friends on bikes would go spread out. I sold them to him for $10-15 to him, and $40 myself.

(Vegas was a much better scalper than me. I watched him flip a four pack of lowers for $80 each right in front of me. I never dared charge that much.

I didn’t have time for accounting, so I just kept huge wads of cash in my pockets.

By five minutes after opening kick I was selling them for $5 each, and by about 20 mins into the game no one was buying, so I took two of the last four (they happened to be great seats) and watched the second half of the game.

All said and done, when I got back to my car I had a wad of $1500 in my pocket. Enough to send half to the original owner of the tickets, pay off the mechanic and tow truck driver, and I went to *Subway* (an absolute luxury at the time).

And that is how I *barely* managed to stay in Silicon Valley to fight another day.

Sometimes we all end up right on the edge of failure. But there’s always a way. Even when it seems like there’s not a way out.

High Agency is about making things work out.

Sometimes a goal doesn’t have a clear path, but, as Sam Parr said…

When you’re driving from San Francisco to New York through the night, you don’t need to see the whole road at once. You just need your headlights to light up the 200ft that’s in front of you.

Identifying high agency in others is relatively simple.

Jeff Bezos asks…

If you were stuck in a third world prison and had to call one person to bust you out, who would you call?

… Which is great when you’re choosing a CTO or you’re a VC investing in a founder (who wouldn’t invest in Lambda School?).

But how do you become High Agency yourself?

Is there a protocol for manifesting High Agency?

High Agents by definition are uniquely resourceful. Once something is repeatable and scaleable, it gets absorbed into the zeitgeist. So copying acts of high agency doesn’t grant you agency.

Quite the opposite.

Copying others makes you reliant on others.

The tricky part is recognising that agency is there for the taking. And then seizing it.

Like wealth, and confidence, and self-awareness, and kindness, agency isn’t limited. The more that exists in the world, the better for everybody.

And now, more than ever, we need agency to unlock human talent at scale.

To unlock that agency, I don’t have a path. Remember there’s no prescription. Coaching and self-help can’t help anybody who doesn’t possess the foundational agency to change. Agency is at the bottom of the stack – it comes from within.

For me, putting a name on it and crystallising the idea was enough to push me towards higher agency. I suspect that high agency is contagious – that it gathers in pools and spreads by contact.

As a reader of Hackerpreneur, chances are you’re already on the right end of the hapless-resourceful spectrum.

My hope is that, as it did for me, exposure to high agency will draw you into it. It’s one of those ideas that turns into small actions, which pay off and compound. Carpe diem.

_

This article originally appeared in issue 34 of Hackerpreneur Magazine.

Finally, it wouldn’t be good form to omit the pieces by Ryan Holiday & George MacGill that I drew from in this essay. Kudos.